Jennie Gilman

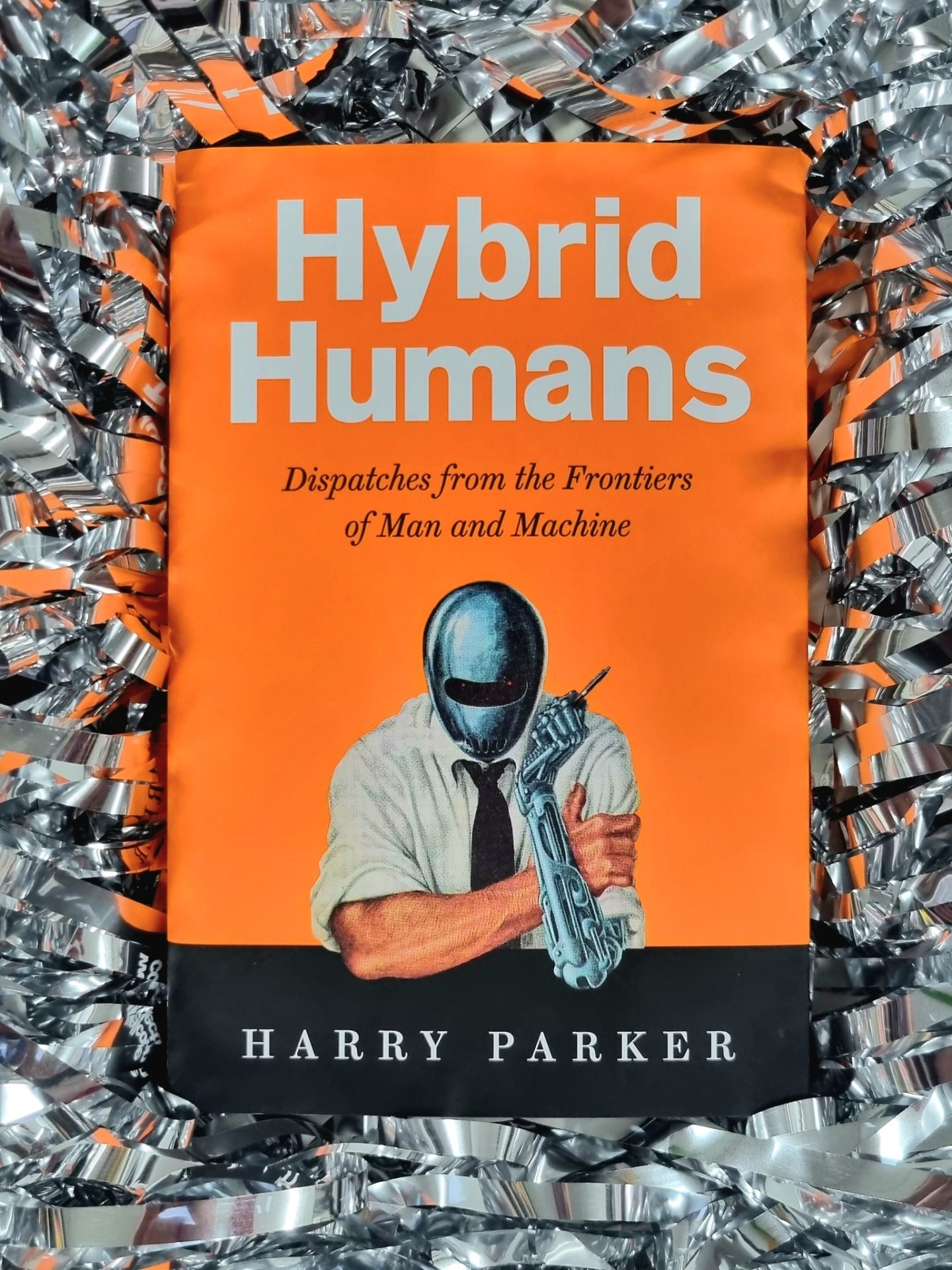

In Hybrid Humans, Harry Parker makes a deeply personal, yet philosophically and scientifically rich case for ‘hybrid human’ as the alternative category needed to describe his own, and potentially our cultural, human-machine symbiosis. Written over a decade on from stepping on an improvised bomb while serving in Afghanistan and subsequently having both legs replaced with prosthetics, Parker’s study wrestles with the inadequate (and often ableist) terms used to describe his new disabled identity.

Parker undertakes a range of conversations with disabled people undergoing life-changing surgery to test the latest assistive technologies such as osseointegration (the permanent fusion of bone with prosthetic) and experimental future technologies such as exoskeletons. Through these, he considers how the use of assistive tech opens two critical and contradictory possibilities.

First, assistive technologies may be used to replace or repair bodily losses so that disabled people can appear to possess the ‘normalcy’ of a complete body, to observe their own embodiment, and to ‘feel like more of a person’ (p.51) again. In other words, they serve humanizing purposes, reaffirming the value of the physical body and embodied cognition to our identity.

Second, and most radically, assistive and implanted technologies represent the possibility of not only repairing the body, but of enhancing it beyond its current scope of abilities. Towards the beginning of the text, Parker states that ‘Cyborg and bionic carry too much baggage; they conjure too many fictions and unrealistic expectations’ (p.21). Despite this initial dismissal of the term cyborg, Parker’s analysis of assistive tech ultimately expresses the contradictory nature embodied by the posthuman itself, ‘the desire to transcend the human while at the same time reasserting the importance of the flesh and the materiality of lived experience’ (Ayers, 2012). While rejecting the cyborg in name, the multiple functions of the term and idea as both normalizing and enhancing are deeply inscribed in the book.

Parker’s project is a modest one. He states that hybrid human is ‘a label just for me, not one I would impose on others’ (p.21), emphasizing that his book is foremost autobiographical account and only secondarily a cultural case study of the relationship between humans and machines. Perhaps, then, a narrative about the lived experience of disability is no place to impose a posthumanist reading. But Parker’s personal story of becoming disabled raises important ethical questions about posthumanist discourse and the problem with imposing homogenizing posthumanist labels onto disabled individuals.

One of the most poignant elements of Hybrid Humans is the way Parker describes the pain of adapting to a new identity and integrating new technologies into his body. He explains how ‘We can extend ourselves to incorporate a tool instinctively […] We are a tool using species’ (p.39) and that the interface between human and technology has in fact been an easy and unconscious evolutionary step. But from his personal perspective of being an amputee, the pain of such an interface, such as phantom sensations, is something most people will never experience. Given its subjective nature, pain both undermines the importance of embodied cognition to posthumanism and reinstates the subjectivity and individualism associated with humanism.

While the painful and violent relation between amputated bodies and technology is unknowable to people who have never undergone these experiences, the visceral descriptions of such sensation serve to reframe the wider human connection with technology as one that is not an easy, evolutionary inevitability, but a hostile development in human Being. The role of violence and suffering in posthuman-becoming through tech is rooted in the militant legacy of the cyborg and cybernetic weaponry reflected in the violent language of the digital ‘invading’ or ‘colonizing’ our lifeworld. Without falling into apocalyptic tales of artificial intelligence’s supremacy, being aware that our dependency on technology may have unforeseen consequences is a crucial practice in protecting our vulnerable agency in a technocratic world.

Harry Parker’s painful journey towards his new human-machine identity, one thrust upon him by a traumatic event, also suggests that to tag someone as a cyborg who does not self-identify as such, to “cyberpunk” someone, if you will, is a linguistically violent act. It is particularly volatile in relation to disabled lives, as it becomes yet another way to quantify, dehumanize, and control them. From Parker’s sceptical encounters with transhumanists in his book, it does not seem too bold to suggest that those who most readily adorn the cyborg badge are those who have never truly experienced the pain, trauma, shame, and possible acceptance of having a disabled body. This may imply that there is an able versus disabled identity binary imbedded in the cyborg name, and that the time for a new category, just as Parker offers, is overdue.

From the perspective of posthumanist scholarship, ‘hybrid human’ arguably says nothing different about the human-technology relationship than ‘cyborg’. It is yet another synonym for our dualistic relationship with machines and does not sufficiently refute the utility of the cyborg as a visual representation of our technologically mediated selves. But for Parker, this relabelling is extremely liberatory. ‘Hybrid human’ allows him to wear his ‘monstrous’ (p.203) bodily transformation as a celebration of difference and resistance to normative categories. But equally as important, the operative word ‘human’ allows him to feel exactly that, in a way that it isn’t compromised by the types of fictions conjured by the word ‘cyborg’. While sweeping sentiments like ‘We are all cyborgs now” make for click-worthy TedTalk titles, they fail to register the value of feeling human when such experience has been taken away from you.

Further Reading

- Drew R. Ayers, Vernacular Posthumanism: Visual Culture and Material Imagination, (George State University, 2012).

- Amber Case, We are all cyborgs now, TED, December 2010, https://www.ted.com/talks/amber_case_we_are_all_cyborgs_now?language=en.

- Dani Cavallaro, Cyberpunk and Cyberculture: Science Fiction and the Work of William Gibson, (London: Athlone Press, 2000).

- Leigh Gilmore, Agency Without Mastery: Chronic Pain and Posthuman Life Writing, (December 2012).

- Harry Parker, Hybrid Humans, (London: Profile Books LTD, 2022).

About the author

Jennie Gilman

@JennieGilman

Jennie Gilman is a research masters student at the University of Leeds with special research interests in posthumanism, immersive storytelling, and digital culture.